Who would have thought a dog and cat that barely moved on screen would be the start of a TV empire?

Who would have thought a dog and cat that barely moved on screen would be the start of a TV empire?

It was on this date, 65 years ago, NBC aired the first Ruff and Reddy Show. It was a rarity, back then, for a Saturday morning. It contained brand-new, never-seen-before cartoons made especially for television.

We’ve written about the series a number of times (see the Topics tree on the right side of this page). To give you a capsule history:

• Rudy Ising claimed he went to Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera at MGM in 1955 with the name and “the format” for the cartoon; they were originally Ising’s “Two Little Pups” at MGM. He sued after the series debuted (see The Hollywood Reporter, June 30, 1958).

• Ruff and Reddy were copyrighted on May 25, 1956 by Shield Productions. This was a company co-owned by Hanna without Barbera (see the U.S. Government Catalog of Copyright Entries and Keith Scott’s book The Moose That Roared).

• H-B Enterprises was registered on July 7, 1957 after MGM closed its cartoon studio. Layout artist Dick Bickenbach told historian Mike Barrier the MGM crew was working on Ruff and Reddy just before the closure.

• NBC buys the series from Screen Gems. The Reporter of Nov. 11, 1957 mentions the show will be in colour “with initial episodes taking them to outer space. Two first-run cartoons from the Columbia library will also be included.”

You can read more about all this, and the copyright episode dates in this post.

What was the first show like? We’re fortunate enough to have a review from Billboard’s Charles Sinclair in the issue of December 23, 1957. It also leaves a hint about one of the Columbia/Screen Gems cartoons that aired.

Ruff and Reddy (Net)

Host, Jimmy Blaine. Producers: Fred Hanna [sic], Joe Barbera. Director, Robert Holtgen. Utilizes cartoons, both new product and former theatrical shorts. A Screen Gems Production for NBC-TV. Sustaining.

(NBC-TV, 11-11:30 a.m., EST, Dec. 14)

“Ruff and Reddy is a slicked-up version of the kind of cartoon show which has often pulled high ratings at the local level when assembled by stations out of available cartoon packages. It may well repeat the same performance in its run on NBC-TV’s Saturday morning line-up.

The format was simplicity itself. Jimmy Blaine, complete with blazer jacket emblazoned with Ruff and Reddy characters on the pocket, gave the lead-ins and lead-outs to a pair of Screen Gems cartoons full of the usual slapstick chases, which in turn sandwiched a cliff-hanger cartoon about the adventures of Ruff and Reddy with space pirates.

Moppet dialers may have been pulled at the clincher in the first cartoon, where a seed-guzzling crowd [sic] stopped ruining a roof garden because it was a “Victory Garden,” but it at least firmly dated the cartoon for adults. A pair of contest plugs, involving Revell electric trains and a doll layout, looked for all the world like regular commercials, complete with “hard sell.”

Summed up: “Ruff and Reddy” should have lots for the tots.

The show wasn’t sustaining for long. Billboard of December 16th reported General Foods bought alternate weeks. The odd thing is Ruff and Reddy was opposite Mighty Mouse on CBS, which was also sponsored by General Foods.

The Columbia cartoon referred to in the review matches the description of “Slay It With Flowers,” a 1943 short starring the Fox and Crow.

The National Parent-Teacher didn’t review the show until its November 1959 issue, but seemed fairly positive about it, though the reviewer had trouble grasping the cliff-hanger aspect.

Ruff and Reddy. NBC.

This is a show designed for “children as children,” not as jet pilots, U.S. marshals, or space men. The scenes are those of Wonderland, the characters whimsical and elfin. Now and then some monster rears his fearsome head, but he’s too fantastic to give rise to more than a short, delicious shudder. Even the commercials manage to adapt themselves to the spirit of the entertainment less clumsily than in most shows where this is tried.

Many of the cartoon sequences have a quality of mystery and charm that suggest the famous Arthur Rackham illustrations for children’s books. Others, alas, are humdrum cartoon staples—not by the artist’s choice, we'll wager, and in future we hope this imaginative cartoonist may be given his head.

The characters have a fine time playing tricks with words (“Mr. Tall met Mr. Small in the hall—that’s all”). A child is sure to follow suit with a perseverance that may drive adults to distraction yet can lay a fine foundation for language skill. But we strongly recommend more caution with the word games. Bad English like “Who am I? You know whom,” “float as good as a boat,” and mispronunciations for the sake of punning (‘“genuwine hareloom,” “‘cat-astrophe”) can make impressions that will take years to come unstuck.

The characters have a fine time playing tricks with words (“Mr. Tall met Mr. Small in the hall—that’s all”). A child is sure to follow suit with a perseverance that may drive adults to distraction yet can lay a fine foundation for language skill. But we strongly recommend more caution with the word games. Bad English like “Who am I? You know whom,” “float as good as a boat,” and mispronunciations for the sake of punning (‘“genuwine hareloom,” “‘cat-astrophe”) can make impressions that will take years to come unstuck.These elements are held together, after a fashion, by a host who is seen briefly with two talking birds—telling a riddle, rattling off amusing nonsense, or raptly reciting his commercials. We say “after a fashion” because the components of the show, delectable as they are, are thrown at the viewer in what appears to be utter confusion. It may go something like this: The birdman introduces a cartoon. The cartoon is interrupted by man-and-bird comment, which is interrupted by a commercial. Then we see another—and different—cartoon. Then there's more man-and-bird comment, with a commercial or maybe two commercials. After that we go back to the first cartoon, which is at last completed, though not without interruption by a song or two and another commercial. Perhaps this confusion doesn’t bother children. They may think that’s the way it is in life and art. But shouldn’t they be finding out that there’s such a thing as form—in art, however it may be in life—and that form begins with unity and continuity?

This lack of wholeness Ruff and Reddy shares with many of the children’s shows, especially those that include cartoons. But surely it is one program that can maintain itself on a higher level. It provides more than passive entertainment for children. It is a show that can teach a child to flutter the wings of fancy. Let it teach him to flutter them in rhythm as well as rhyme.

It didn’t take long for Screen Gems’ marketing people to pounce on the show for tie-ins. The Reporter of December 30 said the show “has already been franchised for a number of toy and clothing items on the basis of previews of the films.”

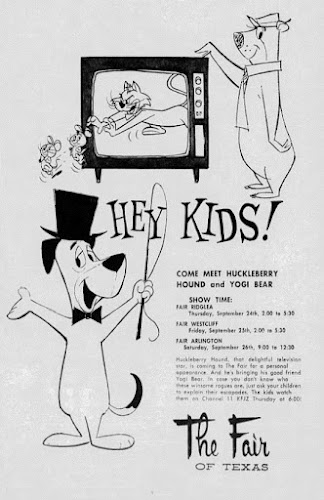

And it didn’t take long for H-B Enterprises to find a new enterprise. Variety of Jan. 22, 1958 mentioned 52 segments of Ruff and Reddy had been completed (the first four adventures of season one) but production had begun a week earlier on 78 segments for a new programme. Talks were underway with Screen Gems on a new series. It was The Huckleberry Hound Show, which racked up favourable reviews, a cult audience (at least in its first year) and an Emmy. Huck, more than Hanna-Barbera’s other drawling dog, gave the studio its major boost.

Now something for you “list” fans out there. Here’s what the Philadelphia Inquirer put in its TV listings for the first run of the first season. No Columbia cartoons are mentioned and there wasn’t a summary every week.

December 14, 1957

(Debut). Kiddies’ cartoon series.

December 21, 1957

Kiddies’ cartoon series.

December 28, 1957

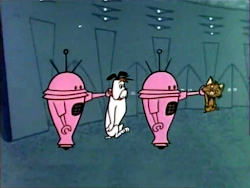

“The Mad Monster of Muni-Mula.” Ruff and Reddy, that crazy cat and dog team, are told by Mr. Big Thinker that he is going to make robots that look like them for his invasion of Earth. “The Hocus Pocus Focus.” When Ruff and his robot-brained pal try to escape, the Thinker orders their return.

January 4, 1958

“Muni-Mula Mix-Up.” When Ruff and Reddy, the dynamic cat and dog, try to escape from the robots on the aluminum planet of Muni-Mula, they are caught by the ever-present Hocus Pocus Focus, which takes them to the Big Thinker, the planet’s leader. The pair, thinking they are sure goners, are surprised when the Big Thinker’s large metal head opens and out pops an unexpected guest.

January 11, 1958

“The Creepy Creature.” Ruff and Reddy, the adventurous cat and dog, held prisoner on the planet Muni-Mula, fall into good luck when they meet Professor Gizmo, who shows them the real master mind of the planet, a mechanical brain. “Surprise in the Skies.” Ruff, Reddy and Professor Gizmo are attacked by the whole Muni-Mula army of robots.

January 18, 1958

“Crowds in the Clouds.” Reddy is accidentally left behind when the adventurous cat-and-dog team, Ruff and Reddy, try to escape from the plant [sic]. Muni-Mula, on Professor Gizmo’s rocket ship. “Reddy’s Space Rescue.” As Reddy falls through Space, Gizmo saves him with his secret weapon.

January 25, 1958

“Rocket Ranger Danger.” After escaping from the aluminum planet, Muni-Mula, Ruff and Reddy, the adventurous cat and dog, and their friend Professor Gizmo, relax in their rocket ship. “African Adventures.” Ruff and Reddy start a new adventure when they agree to help Pinky the pint-size pachyderm, find his mom in Africa.

February 1, 1958

>“Last Trip of the Ghost Ship.” Ruff, Reddy and Pinky the pint-size pachyderm board the ship “Voodoo Queen” headed for Africa. “Irate Pirate.” The trio meet Cross-Bones, the tiny pirate captain who forces them into the brig.

>“Last Trip of the Ghost Ship.” Ruff, Reddy and Pinky the pint-size pachyderm board the ship “Voodoo Queen” headed for Africa. “Irate Pirate.” The trio meet Cross-Bones, the tiny pirate captain who forces them into the brig.

February 8, 1958

“Dynamite Fright.” Ruff, Reddy and Pinky the pint-sized pachyderm escape from the ghost ship’s brig and are thrown into the ocean when the ship blows up. Their raft is attacked by a swordfish. “Marooned in Typhoon Lagoon.” To evade their attacker, Pinky blows a jet of air from his trunk. It propels them to the African shore.

February 15, 1958

“Scarey Harry Safari.” In Africa, Ruff is kidnaped by Harry Safari, the hunter, who uses him for bait. A lion saves him, but in turn is caught in a trap. “Jungle Jitters.” Ruff beats Harry to the trap and saves the lion. Ruff tricks the hunter into giving him his gun. he little cat aims at a rock. But it’s not a rock, it’s Pinky the pint sized pachyderm.

February 22, 1958

“Bungle in the Jungle.” Ruff mistakes Pinky, the elephant, for a rock, but the little elephant is saved when Reddy spoils his friend’s aim. Now it’s Harry Safari’s turn. He takes aim at Pinky, but is scared out of his wits by the friendly lion’s roar. “Miles of Crocodiles.” Ruff, Reddy and Pinky then try to cross a stream by floating some logs. But they’re not logs—they’re crocodiles.

March 1, 1958

“A Creep in the Deep.” Reddy is luckier than Ruff and Pinky the Pint-sized Pachyderm, who are caught on a crocodile-infested river. From a tree, Reddy swings his friends back to shore. “Hot Shot’s Plot.” Harry Safari finally tracks down the trio. He tricks the naïve Pinky into luring his mom toward one of Harry’s traps.

March 8, 1958

“The Gloom of Doom.” Pinky, the pint-sized elephant, realizes too late that he is trapping his mother. Ruff, Reddy and the friendly lion rush to her air, but they are soon at the mercy of Harry Safari.

March 15, 1958

“Introduction—Western Adventure.” Ruff and Reddy, the powerhouse cat and dog duo, embark on a western vacation when Reddy wins a limerick contest. They head for the Grand Canyon, but take a wrong turn, and wind up in the spooky ghost town of Gruesom Gulch. “Slight Fright of a Moonlight Night.” After meeting some of the frightening spectres who haunt Gruesome Gulch, Ruff and Reddy head for the sheriff’s office.

March 22, 1958

“Asleep While a Creep Steals Sheep.” Ruff and Reddy, the adventurous cat and dog, meet a long-haired sheep dog with a mystery to unfold. Hijackers have been rustling his flock without leaving tracks. Reddy masquerades as a sheep, hoping to catch the outlaws red-handed, but falls asleep on the job. “Copped By a ‘Copter.” Reddy, disguised as a sheep, is hauled into a helicopter by two desperadoes.

March 29, 1958

“The Two Terrible Twins From Texas.” Reddy, the canine half of the cat and dog team, Ruff and Reddy, has been kidnaped by two fierce outlaws who think he’s a sheep. They discover his identity, and whisk him away in their helicopter before his pal, Ruff, can come to the rescue. “Killer and Diller.” The notorious outlaws, Killer and Diller, dream up a gruesome scheme for getting rid of Reddy. They fly him to Dead Man’s Mine, then send him rolling on his “last ride” in a runaway ore car.

April 5, 1958

“A Friend to the End.” Reddy, the drawling dog, is being hurtled to certain destruction in a runaway ore car, when his pal, Ruff, comes to the rescue. Then they head for the boarded-up shack where rustlers Killer and Diller have hidden the stolen sheep. “Heels on Wheels.” The walls of the old shack slide apart, and the outlaws speed out of the building. Ruff and Reddy decide to follow by helicopter, but there’s one small problem. Reddy, the pilot, has never flown before.

April 12, 1958

“The Whirly Bird Catches the Worm.” The heroic cat and dog team, Ruff and Reddy, use a helicopter to chase a pair of escaping sheep rustlers. When the outlaws stop for a quick lunch, Reddy swoops down on them, parking his ‘copter on the rustlers’ moving truck. “The Boss of Double Cross.” Reddy daring jumps from the helicopter to the roof of the speeding truck, but doesn’t realize there’s a tunnel dead ahead. He’s knocked out cold, and the outlaws make a bee-line for their headquarters, the notorious Double-Cross Ranch.

April 19, 1958

“Ship Shake Sheep.” Ruff and Reddy, searching for a flock of stolen sheep by helicopter, discover the hideout of the sheep-nappers, Killer and Diller. The helicopter is about to crash, but the quick witted sheep band together to spell out a warning to their rescuers. When Ruff and Reddy parachute to the ground, the rustlers are waiting for them. “Rootin’ Tootin’ Shootin’.” Reddy is talked into observing the “code of the west” and shooting it out with a killer. The outlaw reaches for his “12 gun” and gives Reddy a frightening demonstration of plain and fancy shooting.

“Ship Shake Sheep.” Ruff and Reddy, searching for a flock of stolen sheep by helicopter, discover the hideout of the sheep-nappers, Killer and Diller. The helicopter is about to crash, but the quick witted sheep band together to spell out a warning to their rescuers. When Ruff and Reddy parachute to the ground, the rustlers are waiting for them. “Rootin’ Tootin’ Shootin’.” Reddy is talked into observing the “code of the west” and shooting it out with a killer. The outlaw reaches for his “12 gun” and gives Reddy a frightening demonstration of plain and fancy shooting.

April 26, 1958

“Hot Lead For a Hot Head.” Reddy, the awkward pooch, prepares to shoot it out with those notorious gunslingers, the Terrible Twins from Texas.

May 3, 1958

“Blunder Down Under.” Ruff and Reddy,” the adventurous cat and dog, dive into the ocean to catch a slippery seal, but encounter a strange metal monstrosity, which rises mechanically out of the sea.

May 10, 1958

“The Late, Late Pieces of Night.” Ruff and Reddy set out to sea on Professor Gizmo’s boat, the S. S. Leadbottom, but a strange submarine follows them all the way. They reach Doubloon Lagoon, and discover a sunken chest filled with pieces of eight. “The Goon of Doubloon Lagoon.” The diving bell, with Ruff and Reddy inside, is captured by mysterious magnetic rays from a phantom submarine. Our heroes are whisked off to Gruesome Grotto, a secret hideaway beneath the sea.

May 17, 1958

“Two Dubs in a Sub.” Ruff and Reddy, the foolhardy cat and dog, are tossed into a cell at “Gruesome Grotto,” the underwater hideaway by a pair of sea going swindlers, Captain Greedy and Salt Water Daffy. Their faithful friend, the seal, attempts to rescue them. “Big Deal with a Small Seal.” Ruff and Reddy, along with Professor Gizmo, are trapped in a cell—and the walls are moving in to crush them. But their pal the seal stops the torture device.

“Two Dubs in a Sub.” Ruff and Reddy, the foolhardy cat and dog, are tossed into a cell at “Gruesome Grotto,” the underwater hideaway by a pair of sea going swindlers, Captain Greedy and Salt Water Daffy. Their faithful friend, the seal, attempts to rescue them. “Big Deal with a Small Seal.” Ruff and Reddy, along with Professor Gizmo, are trapped in a cell—and the walls are moving in to crush them. But their pal the seal stops the torture device.

May 24, 1958

“A Real Keen Submarine.” Ruff and Reddy, the happy-go-lucky cat and dog, try to escape from Captain Greedy in the Captain’s own submarine, but Reddy and his slippery pal, the seal, are captured. The seal slides away from Greedy’s clutches, and the chase is on. “No Hope for a Dope on a Periscope.” Reddy is hanging onto the periscope of the submerging sub, but the seal comes to the rescue. He drags the water logged dog to shore just in time to encounter, once again, the giggling pirate, Salt Water Daffy.

May 31, 1958

“Rescue in the Deep Blue.” While Ruff, the feline half of the cat and dog duo, Ruff and Reddy, is forced to help Captain Greedy dig for sunken gold, his partner, Reddy, is held prisoner at Gruesome Grotto. Reddy makes his get-away, but he’s trailed by a dog eating shark. “A Whale of a Tale of a Tail of a Whale.” Reddy and his friend, the seal, come ashore on a small island, which turns out to be a big while. They hitch a whale-back ride to Doubloon Lagoon where Captain Greedy has Ruff doing his dirty work.

June 7, 1958

“Welcome Guest in a Treasure Chest.” Ruff, the spunky cat, thinks his partner, Reddy, the dumpy dog, has been swallowed up in the briny deep and continues to work for the pirate, Captain Greedy. But the shrewd seal, Ruff and Reddy’s slippery pal, has a plan for fooling the evil captain by hiding a sunken chest. “Pot Shots Puts Hot Shots on Hot Spot.” Captain Greedy and Salt Water Daffy steal the S. S. Leadbottom and load it with pirate gold—leaving Ruff and Reddy off on a desert island.

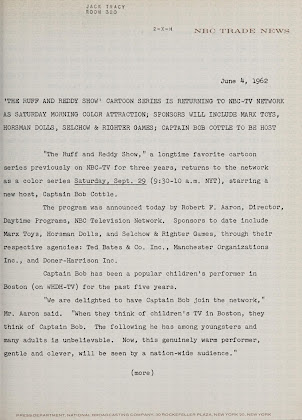

Here are two NBC news releases, one outlining reruns in season one and the other announcing the start of season two. You can click to enlarge them.

The Chicago Tribune published on October 4, 1958, the date of the last show in season one, listed the Columbia cartoon as Carnival Courage (1945).

NBC continued carrying the series for another two seasons, but the number of Ruff and Reddy cartoons was expanded from two to three. One newspaper’s listings for Saturday, October 18, 1958 gives the names of fourth, fifth and sixth episodes of the chickasaurus story, meaning the first three ran to start season two a week earlier. The Columbia cartoons may have disappeared. A network news release dated May 15, 1959 stated broadcasts of The Ruff and Reddy Show would begin in colour on June 6, 1959. It seems that was postponed until June 27th, according to a release dated June 2nd, which bragged about the colours on Jimmy Blaine’s puppets, Jose the toucan and Rhubarb the parrot.

NBC continued carrying the series for another two seasons, but the number of Ruff and Reddy cartoons was expanded from two to three. One newspaper’s listings for Saturday, October 18, 1958 gives the names of fourth, fifth and sixth episodes of the chickasaurus story, meaning the first three ran to start season two a week earlier. The Columbia cartoons may have disappeared. A network news release dated May 15, 1959 stated broadcasts of The Ruff and Reddy Show would begin in colour on June 6, 1959. It seems that was postponed until June 27th, according to a release dated June 2nd, which bragged about the colours on Jimmy Blaine’s puppets, Jose the toucan and Rhubarb the parrot.

Ruff and Reddy disappeared from the schedule after summer of 1960 but returned for the 1962-63 and 1963-64 seasons. You can read the release from NBC below. Note that Blaine was gone.

The last Ruff and Reddy show on NBC on Saturday mornings appears to have aired on September 26, 1964. The cartoons soon popped up in syndication, judging by TV listings in late 1964, including on KCOP Los Angeles with Bob Adkins as a host. Years later, American readers of a certain age will remember when cable television erupted, the cartoons appeared on Boomerang.

I’ve said a number of times I’m not a fan of the show and don’t recall watching it when I was a kid. Regardless, it does deserve some recognition for historical reasons, as well as some really good background art and music selection, but I imagine it’ll be yet another old H-B series that we won’t be seeing on home video.