I caught most of the seasons in first-run and then every weekday through the latter part of the 1960s in syndication. To explain what I liked about the show, I have to explain what I didn’t like about the show.

I caught most of the seasons in first-run and then every weekday through the latter part of the 1960s in syndication. To explain what I liked about the show, I have to explain what I didn’t like about the show.The worst episode was when Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm unexpectedly sprouted voices and constantly sang an annoying and insipid song. As the episode unfolded, I couldn’t believe what I was watching. The fact it turned out to be a dream struck me, age nine or so, as an outrageous attempt to screw with my head and add sense to a nonsensical idea.

And that anomaly speaks to the reason about why The Flintstones has been popular all these years. The characters are believable.

They behave in a way we all recognise. Who doesn’t know at least a toned-down version of a loud guy who thinks he has all the answers but, at the same time, has a softer side he doesn’t like showing? Or a friend who’s happy-go-lucky, if not a little goofy? Or an enthusiastic pet that seems to take on human qualities? Crappy work-days, lack of money, trying to find time for simple recreation, being wide-eyed at Hollywood hype, raising a kid. The Flintstones treated them with humour and occasional lampoonery. Viewers understood, empathised and believed.

Yes, we all know no one ever used talking mastodons as kitchen hoses. But that’s believable, too. The show follows a certain logic—it’s set in the Stone Age, so what else would they use? So we’re willing to accept a talking bird as an intercom or a little tyrannosaurus as a lawnmower. And an extra element has been added. They act almost as a Greek chorus, talking to us about the previous dialogue or their lot in life, much like Warner Bros. cartoon characters making weary or silly (but always pertinent) asides to the audience.

And for young viewers like me, there was an added bonus. The Flintstones reinforced our belief adults sometimes did a lot of really stupid things. Kids wouldn’t do them. That meant we were smarter.

To pull it all together, Joe Barbera put together a stellar cast of actors—Alan Reed, Mel Blanc, Jean Vander Pyl and Bea Benadaret, ably assisted by Don Messick, John Stephenson, Hal Smith and a bunch of others, including radio’s incomparable battle-axe, Verna Felton.

To pull it all together, Joe Barbera put together a stellar cast of actors—Alan Reed, Mel Blanc, Jean Vander Pyl and Bea Benadaret, ably assisted by Don Messick, John Stephenson, Hal Smith and a bunch of others, including radio’s incomparable battle-axe, Verna Felton.You’ve read the rippings the critics gave the show after its first broadcast. Let’s jump ahead of October 4, 1963. No less than Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times, the paper that called The Flintstones “an inked disaster” in Jack Gould’s column three years earlier, praised the show and elucidated his reasons far better than I have. I can only wonder what Gould must have thought of his co-workers’ words.

Cartoon Flintstones Possess Freshness Rarely Found in Acted TV Comedy

SINCE Actors Equity has co-existed with animated cartoons through most of its history, it has taken no official action against “The Flintstones,” now in its fourth season on American Broadcasting Company television.

But the comedians’ section of Equity might consider a suit on grounds of unfair competition. No actor could duplicate the exuberant frenzy of Fred Flintstone, the Stone Age extrovert whose combination of bullheadedness and blundering—both in an excessive degree—is the weekly topic of a remarkably fresh cartoon. “Barney, you know I never have any trouble sleeping,” Fred once gloomily observed to his pint-size buddy. “It’s when I am awake that my troubles begin.” Fred is a rugged individualist with a feeble brain-bone.

If the cartoon elements could be scientifically analyzed, they would probably emerge as a version of the familiar big-man, little-man comedy—Mutt and Jeff, Bert and Harry Piel, etc. But William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, who invented the characters in 1960, lifted their cartoon out of mediocrity by setting it in the Stone Age. It is pure fantasy in the genre of “Alice in Wonderland.” Although the Flintstones, and their next-door neighbors, the Rubbles, lead modern lives with modern equipment, they are Stone Age people who have domesticated Stone Age animals and birds to perform the household chores.

AS A CRANE operator in the Rock Head and Quarry Construction Company, situated in Bedrock, Fred drives a patient dinosaur. The current introduction to the program pictures Fred sliding joyously down the back of the dinosaur when the whistle blows and yelling “ya-ba-ba-ba-doo,” which is his theme cry. The family pet in the home cave is a young dinosaur that obeys Fred’s “Down, boy” literally by knocking Fred down and smothering him with kisses.

A starving buzzard under the sink is the garbage disposal, and an elephant’s trunk is the kitchen faucet; a lizard with sharp teeth is the can opener; a mastodon with an evil look is the vacuum cleaner; a bitter crow with a sharp beak is the needle on the hi-fi set; a pterodactyl with gnashing teeth and a mean disposition is the lawn mower.

A starving buzzard under the sink is the garbage disposal, and an elephant’s trunk is the kitchen faucet; a lizard with sharp teeth is the can opener; a mastodon with an evil look is the vacuum cleaner; a bitter crow with a sharp beak is the needle on the hi-fi set; a pterodactyl with gnashing teeth and a mean disposition is the lawn mower.During the last season, “The Flintstones” lost some of its original enthusiasm for the fantastic setting. It has become increasingly preoccupied with domestic affairs, like the birth of a bland, self-contained daughter, Pebbles, to Fred and Wilma (Isn’t Pebbles rather large for her age?) But the original genius of the cartoon was the comic ingenuity with which it played variations on the incongruous, inventive and humorous background of the Stone Age.

The traditional business of cartoons is to explore the battle between the sexes. After losing one round to Wilma recently, Fred said: "Why doesn't someone invent something but women for us to marry?" Both Wilma Flintstone and Betty Rubble are more sophisticated than their husbands and take appropriate action in defense of their prerogatives when necessary. There is nothing mean about any of them. But an ominous drop of sentimentality intruded on domestic dissonance the other day. After Fred had worn himself out trying to look after the baby and the house simultaneously, Wilma said: “Fred, you are the dearest bungler in the world.” This expression of mawkish affection in a cartoon is wholly untraditional.

The traditional business of cartoons is to explore the battle between the sexes. After losing one round to Wilma recently, Fred said: "Why doesn't someone invent something but women for us to marry?" Both Wilma Flintstone and Betty Rubble are more sophisticated than their husbands and take appropriate action in defense of their prerogatives when necessary. There is nothing mean about any of them. But an ominous drop of sentimentality intruded on domestic dissonance the other day. After Fred had worn himself out trying to look after the baby and the house simultaneously, Wilma said: “Fred, you are the dearest bungler in the world.” This expression of mawkish affection in a cartoon is wholly untraditional.A sentimental cartoon is a contradiction in terms. It is getting close to the stuff that human beings act. On the drawing board, Fred and Barney are outside human scale. Everything they do is excessive. In their Stone Age model T they bounce through a grotesque landscape with superhuman speed and utility. At the meetings of the Order of Water Buffaloes they luxuriate superhuman gusto. Thanks to raciness of the cartoon medium, they are worth a hundred of the standard comedies, and they make actors look inept and anxious.

ABC got six prime-time seasons out of the Bedrock gang and that was a little too long. Anyone who has watched TV situation comedies—and I had seen plenty of them before reaching my teenage years—knows when a show has run out of ideas or originality. That’s what happened with The Flintstones. The Rubbles got a pet and a child. The show did that already. The Gruesomes? Too much of a direct copy; anyone could come up with that. Darrin and Samantha Stevens. In the Stone Age? And as cartoons? The Great Gazoo. Can’t the principal characters carry the plot any more? What show needs an unlikable twerp?

ABC got six prime-time seasons out of the Bedrock gang and that was a little too long. Anyone who has watched TV situation comedies—and I had seen plenty of them before reaching my teenage years—knows when a show has run out of ideas or originality. That’s what happened with The Flintstones. The Rubbles got a pet and a child. The show did that already. The Gruesomes? Too much of a direct copy; anyone could come up with that. Darrin and Samantha Stevens. In the Stone Age? And as cartoons? The Great Gazoo. Can’t the principal characters carry the plot any more? What show needs an unlikable twerp?Sorry, but stuff like that hurt the crux of the series’ popularity—its believability.

Normally, missteps like that would kill a show. However, it seems to me there was still enough good to overcome the bad in the old episodes that were rerun endlessly so that the Bedrock gang was still entertaining to millions as the years rolled on.

But The Flintstones is more than a cartoon and more than a cash cow through commercial tie-ins. It’s become a cultural reference point. The show, the characters, even the situations still come up in every day life. Stone Age references generally invoke the name of the show. So did a recent news story about a foot-powered car. A strong football player recently got tagged with a nickname belonging to a boy Bedrock tyke born long before he was. The Flintstones aren’t alone in this. Read any story about flying cars or futuristic homes and you’ll see the word “Jetsons” somewhere. News items about hungry or friendly bears include “Yogi” or “pic-a-nic” (Daws Butler’s contribution to the vernacular). Even Huckleberry Hound and Quick Draw McGraw are still used as comparative examples to people or events because they are known and liked. Their lasting popularity is proof of the skill of the many creative people at Hanna-Barbera through the ‘50s and into the ‘60s to overcome the artistic limitations imposed by television on time and money to create lasting entertainment and fun, believable characters.

Like many of you, I’ve been watching The Flintstones for as long as I can remember. It’s not my favourite Hanna-Barbera show, but the best episodes are still engaging and funny, 50 years later. And you can believe that.

Here are a few news stories you can check out. The first talks about Google’s salute to Hanna-Barbera’s biggest success of the ’60s with a special masthead today. Animation writer Harry McCracken has pointed out Bamm-Bamm’s severed head is on the roof.

A blog on The Toronto Star has a humorous look at what we’ve learned from The Flintstones in 50 years. Apparently, people in Toronto must have humour because the writer states she likes Gazoo. That’s a hot one!

Agence France Presse has a nice summary of 50 years of Life in Bedrock (en Anglais).

Try your hand at a Flintstones Quiz, courtesy of Stony Browntosaurus at the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Want your own Flintstones car? Some guy has actually designed one.

And here’s a site that links to four Flintstone flash games you can play.

Oh, yes, what would the Yowp blog be without cartoon music?

You want background music? Here’s 18-plus minutes of Hoyt Curtin’s incidental music from the seasons before that god-awful compressed crap from Magilla Gorilla inflicted the soundtrack. Lots of bassoons and tubas to provide an earthy sound.

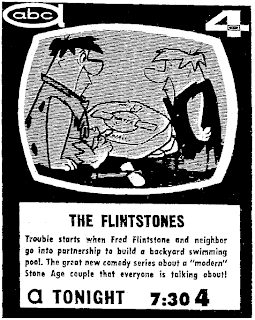

Remember the party music in the first produced cartoon, ‘The Swimming Pool’? You can hear it below, along with some other cool jazzy music. It’s the best stuff Curtin wrote for Fred and Barney. The trumpet playing is wild. Pete Candoli, I’ll bet.

And from Wonderland Records LP-285 is an original cast recording of the second Flintstones theme that the world knows and loves, with an extra chorus and a few different words. Everyone’s singing in character, though Bea Benaderet is actually sing/speaking, despite the fact she sang on stage and when she began in radio in the ‘20s. Alan Reed struggles a bit. Have a listen and have a gay old time. You know what we mean.

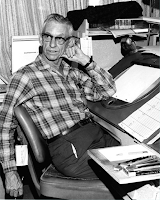

Finally, let us dedicate this post to Warren Foster. You all know Foster’s background. He ran a music school in New York City then got a job with the Fleischer studio. Mike Maltese recommended him to (likely) Bob Clampett and Foster travelled west to the Warner Bros. studio where he and Maltese wrote some of the funniest cartoons ever made. The two were lured to Hanna-Barbera and adapted nicely to the limits of TV animation. Foster maintained a little cynical streak toward show business and marriage which fit in nicely at H-B. I believe he’s with Alan Dinehart in the photo you see here, with one of his fine storyboards in the background. Maltese may be my favourite writer, but it was Foster’s workhorse efforts that helped ensure The Flintstones were a hit.

Finally, let us dedicate this post to Warren Foster. You all know Foster’s background. He ran a music school in New York City then got a job with the Fleischer studio. Mike Maltese recommended him to (likely) Bob Clampett and Foster travelled west to the Warner Bros. studio where he and Maltese wrote some of the funniest cartoons ever made. The two were lured to Hanna-Barbera and adapted nicely to the limits of TV animation. Foster maintained a little cynical streak toward show business and marriage which fit in nicely at H-B. I believe he’s with Alan Dinehart in the photo you see here, with one of his fine storyboards in the background. Maltese may be my favourite writer, but it was Foster’s workhorse efforts that helped ensure The Flintstones were a hit.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)